Long Distance Course Measurement

Long Distance Course Measurement

If there’s one thing about a long-distance race, it’s that it is a long distance! And one of the things that becomes harder with increasing distance is precision of measuring, so how do you know that marathon you just ran, with all its twists and turns, really was 42,195 metres long?

Well, it probably wasn’t EXACTLY that long, but with a maximum margin for error of just 0.1% it will be as near as makes no difference real – between 42,195 and 42,279 metres (yes, that’s a 0.2% increase).

Not all races are certified as accurately measured as it costs money and takes time so isn’t important to all organisers (mainly smaller, local races) – that doesn’t mean that the course won’t be accurate, just that it may not be certified as such.

Note, this only applies to road (or similar) races of fixed length. Off-road or multi-terrain races cannot be measured using this method and those of non-fixed length, such as 12/24 hour races, do not need to be of certified length.

Why bother getting the course certified?

Some need to. Races that are run under association certification (UKA or ARC for instance) will need to have their distance certified as a condition of obtaining a race license.

For others, having a certified course may be more attractive to potential entrants due to the suitability for a PB – uncertified courses aren’t eligible for official records and people are often reluctant to count the result of an uncertified course as their own PB. Some people won’t even enter races that aren’t on a certified route as they want to know for sure they are running the distance advertised.

A certified course gives the race a more ‘official’ feel which attracts entrants.

Would you accept a PB on a course that might have been 500 metres short? Have you run a marathon if the one you ran was a little short of full distance? The answers will differ from person to person.

How courses are measured

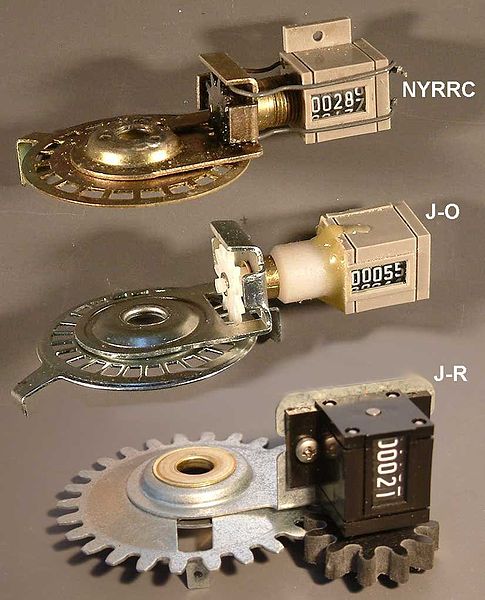

Road courses are measured by according to IAAF procedures which involves an official course measurer cycling the route with a correctly calibrated bicycle that includes a wheel revolution counter, called a Jones Counter.

The calibration process involves knowing the exact circumference of the wheel by counting how many turns it takes to travel a known distance. The measurer needs to factor in tyre pressure, changes in temperature, weather (wet roads cool tyres down) and the road surface of the calibration course vs the course route.

All these things can have an impact on the tyre pressure which will very slightly change the circumference and therefore the distance travelled per rotation. Calibration is done before and after measurement to ensure condition changes haven’t affected the measurement.

Following this process allows for measuring very accurately to within the standard accuracy of 0.1% or 1 metre in every kilometre.

The process of measuring is, in theory, quite straightforward - ride the course along the shortest route and take a measurement. But there are challenges – parked cars, closed gates and other people/riders in the way, not to mention that measuring on open roads can be dangerous – All the types of problem the measurer must take into consideration and mostly ones that have process to resolve.

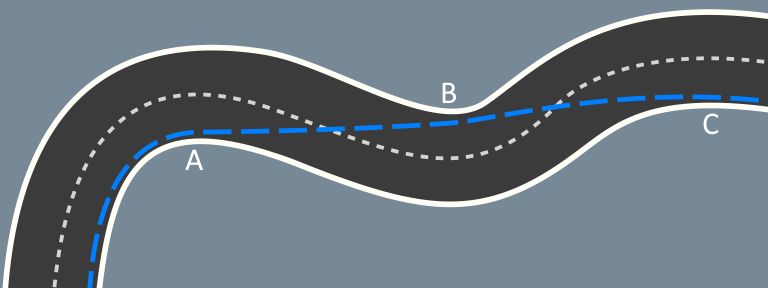

The course will be ridden 2 or more times to ensure an accurate measurement is taken and will be measured along the shortest possible route which means riding tangents and staying 30cm from the inside edge of corners (the kerb or other course boundary).

Above shows the basic line taken through bends, cornering tightly through bends A and C but not quite touching bend B.

The shortest route along a road may also involve using the pavements round corners (or other adjacent areas such as hard verges) that weren’t intended to be run on, that is if the organisers haven’t put in suitable protection to stop runners doing the same thing; If the route requires all runners to run on the road around a corner, what is stopping them stepping up onto the pavement and cutting a little bit off? This done several times along a course can make for a noticeable distance saving.

Kenneth Allen / Runners, Killyclogher 10 K Race (3) [CC BY-SA 2.0]

Kenneth Allen / Runners, Killyclogher 10 K Race (3) [CC BY-SA 2.0]

Was the above course measured around that corner on the road or on the path? If it was the road then some runners are taking a shot-cut, if it was the path then some are running further than they need.

Accuracy

All measuring has a margin for error which for course measurement as mentioned above, is 0.1%. Race certification actually has to ensure that the course isn’t too short so the course will have a “short course prevention factor” added to it to make sure this isn’t the case.

That is simpler than it sounds and all it takes is to add on 0.1% to the distance of the race.

Wait, so that means races are deliberately measured too long?

Yes! A 10k is expected to be 10,010 metres which is enough to compensate for the margin for error in measuring and guarantee that it is not short. This means that the course will actually be somewhere between 10,000 and 10,020 metres long (0.1% either side of 10,010 metres).

A half marathon will have 21 metres added to give a final distance of between 21,098 and 21,140 metres and a marathon 42 metres extra to give a final distance of between 42,195 and 42,279 metres.

But don’t worry if you think you will notice this extra, it’s all much more accurate than your average GPS watch and you will most likely run much further by not running the shortest route as measured.

Full a full, in-depth understanding of course measurement, see the IAAF-AIMS booklet The Measurement of Road Race Courses.

With the course itself being accurately measured, things can still occasionally go wrong, all it takes is a misplaced cone or misread instruction while setting out the course to ruin the perfectly planned and measured course!